The Unsung Heroes: Celebrating Our PTA Volunteers

This month, we celebrate Volunteer Appreciation Week, taking place April 21-27, which is a time to recognize the extraordinary individuals who dedicate their time…

Read More

This month, we celebrate Volunteer Appreciation Week, taking place April 21-27, which is a time to recognize the extraordinary individuals who dedicate their time…

Read More

Volunteer Appreciation Week, taking place April 21-27, is a fantastic opportunity to instill the spirit of giving in your child. It’s a chance for…

Read More

PTA fundraisers are essential to helping schools support student activities inside the classroom and out, build stronger community ties and promote a culture of…

Read More

Every year, students across the country and in U.S. schools abroad participate in the Reflections Theme Search Contest – a competition where students submit…

Read More

February is Black History Month, a time to celebrate the many achievements and contributions of Black Americans throughout our country’s history. In education, many…

Read More

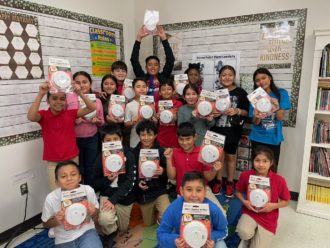

Winnetka Elementary School in Dallas was one of three schools to kick off a new fire safety effort with National PTA and Kidde this…

Read More

With support from Kidde, a Proud National PTA sponsor, local PTAs deliver critical education about fire safety. “Fire safety is not something that’s frequently…

Read More

Every year, hundreds of thousands of students across the country and in U.S. schools abroad participate in the National PTA Reflections program. By creating opportunities for recognition and access to…

Read More

The 2023 National PTA Phoebe Apperson Hearst Award recipients led their School of Excellence programs with the goal of transforming family engagement in their…

Read More

As the New Year approaches, many people start making resolutions to change something about their lives. But, by February, nearly 80% of people will…

Read More